Selecting Content

Choosing a Variety of Resources

The path to learning is paved with content.

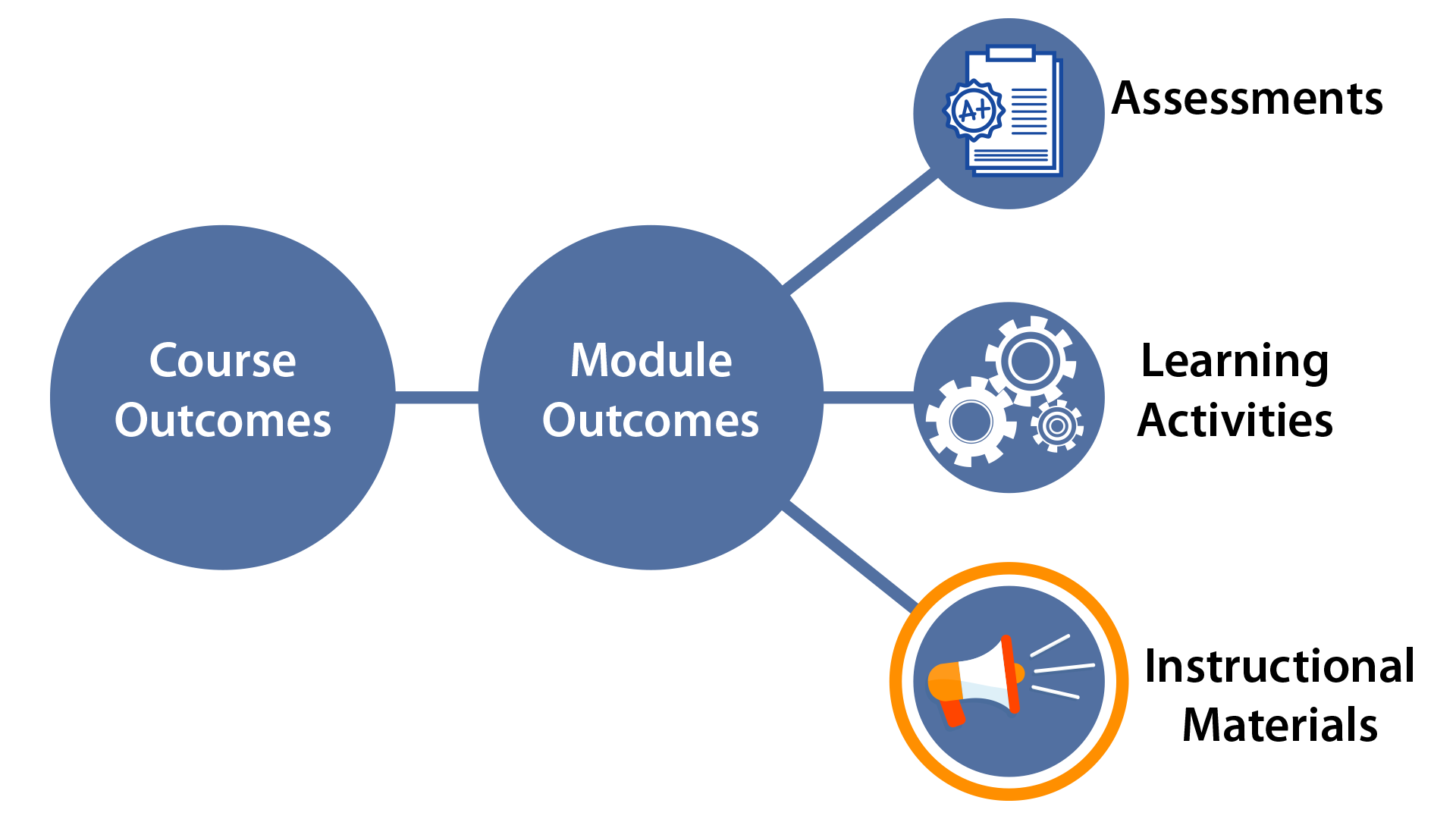

Learning outcomes communicate the goals for a course, and assessments mark progress and achievement, but students need appropriate exposure to activities and instructional materials. Course content is guided by course outcomes and assessments and offers specific knowledge and background that students can use to truly and fully participate and engage in a course.

Course content is the selection of instructional resources by faculty to promote learning, engagement, and achievement of learning outcomes – this includes various multimedia, readings, educational resources, and formative assessments.

Stage Three of Backward Design is the planning of learning experiences and instruction – the content and activities of a course (Wiggins & McTighe, 2005). However, there should always be clear and direct alignment connecting all three stages (outcomes, assessments, and content).

Not only is alignment a best practice in course design, it also gives students insight as to how each assessment, activity, reading, video, or other resource is helping them complete the course. They are motivated when they find relevance in content (Frymier & Shulman, 1995). Students are more apt to read an assigned video if they see ways it is applicable and relevant to their success, degree program and future career.

Consider making these connections for students by indicating how each learning outcome is met by each activity, reading, and resource in your course. Varied forms of content also capture students’ attention and facilitate learning.

SUNY Empire uses a quality course review rubric adapted from the SUNY Online Course Quality Review Rubric (OSCQR). OSCQR’s Standard #29 recognizes the importance of content alignment and the benefit of “access to a variety of engaging resources that facilitate communication and collaboration, deliver content, and support learning and engagement.”

Regardless of the format you choose, e.g. videos, textbook, articles, “it is important to ensure that the learning outcomes are supported and there is a balance, variety, and opportunity for students to engage with the topic in a manner that will assist them in mastering the stated outcomes” (UNTUNT Teaching Commons).

Support Learners with Content

Effective course design begins with the student in mind. Learner-centered course design focuses on meeting students’ needs and goals and is fundamental in content selection and delivery. The framework places the learner as the “chief agent in the process” within “cooperative, collaborative, and supportive” environments (Barr and Tagg, 2005). An example of a student-centered strategy requires students to take notes on content, watch videos, and focus on their needs; students using this method scored significantly higher on course exams (Connell, Donovan & Chambers, 2016). This active learning method also highlights the importance of content variety and involves students in their own learning. Students also perceive greater economic and educational value in this design approach (Nicklen et al., 2016).

Pacansky-Brock’s (2014) YouTube video How to Design Your Online Course demonstrates Backward Design to show student-centered learning results from the alignment of learning objectives with relevant activities and clear assessment methods and can be achieved through the following 3 Steps to Design Your Online Course:

- Identify desired outcomes. What do you want them to know?

- Determine acceptable evidence. How will you know that they have learned?

- Plan learning experiences and facilitation. What will they do? How will they develop and demonstrate the desired outcomes?

Demonstrate Content Alignment

Consider the following example:

Module 1 Readings and Resources

Required:

- Textbook: Chapters 1-2 – these chapters provide the foundational knowledge and will help you understand the main concepts discussed in this module.

- Video: Title (5 min) – in this video the concept of something is introduced, as well as some examples of applications of these concepts. This resource will help you with the assignment in this module.

- Article: Title – this resource reviews the concept of something and provides real world examples. As you read this article, consider the following question as you read it: “Question”.

Additional Support (Optional):

- Article: Title – this article discusses the topic of something in more detail.

- Video: Title (10 min) – this article provides an overview of the different approaches and will help you as you complete the activities in this module.

Resources and Best Practices when Choosing Content

- Accessibility – the delivery of content should always be accessible, providing alternative modes of delivery: transcripts, descriptive text, speech-reader capability, searchable text, etc. Please review the Accessibility section of this site for more information or reach out to the Instructional Design Team if you have specific questions.

- Balance – while the alignment should help you determine what is the essential information versus extraneous information that may not contribute to the objective of the course, another best practice is to explain how the resources going to help to achieve learning outcomes. This practice will also help you assess the relevance of the resource.

- The OSCQR website has details and videos on Standard #29 and others relating to Content and Activities.

- ESC’s Kaltura Capture and LEARNScape can be used to deliver announcements, instruction, and guidance to students. An increase in instructors’ social presence through asynchronous video communication provides students the opportunity to develop an emotional connection and “perceive the teacher as a real person” (Borup, West & Graham, 2012).

- SUNY ESC’s Online Library offers article and journal databases, access to books and multimedia, research resources, and expert librarian support.

- Open Education Resources (OER) are free, openly licensed content. Ready-to-adopt courses and content are available through SUNY OER Services. Interested in getting started with OER? Visit Using Open Educational Resources.

- Carnegie Mellon University’s Eberly Center discusses the importance of aligning assessments, learning objectives, and instructional strategies and provides examples of outcomes and well-aligned assessments to inspire your content selection.

- National Institute for Learning Outcomes Assessment shares an overview of alignment of outcomes with assessments, which features course design examples, including an overview of SUNY ESC’s Grief and Loss course (Muller and colleagues, 2019).

Avoiding Powerpoint

PowerPoint is widely used in the face to face classrooms to convey the main points of a lesson and provide visuals to accompany a lecture. According to Hopper and Waugh (2014), many instructors choose PowerPoint due to the prevalence of the tool in education and time constraints encountered by educators.

Utilizing a PowerPoint slide set for asynchronous online instruction provides a vastly different experience than when it is used to support an in-person lecture. Slides are often presented to the learners without accompanying audio or video lectures to provide context for the information. While slides may summarize and highlight points from the textbook or readings, they don’t expand upon the subject or encourage students to make connections. Using PowerPoint files forces students outside of the learning management system, where they can encounter technical and accessibility issues (Evans & Champion, 2007).

Here are some alternatives to consider when thinking about how to convey course concepts to students in a format other than PowerPoint:

Use Moodle pages to convert slide sets that are text heavy. These pages can be created directly within Moodle and should make use of the appropriate HTML formatting for headings, subtitles, and bulleted or numbered lists. This will make the content more accessible for all students.

Visual information that lacks context can be transitioned to a video with a voice over narration. This enables the content to be explained to the viewer by the instructor. Be sure to consider the multimedia design principles and include descriptive language and captions.

Explore visualization tools to present data charts and graphs. Diagrams can be transitioned to interactive media that allows learners to examine components and explore relationships.

Choosing a Variety of Resources

When you are ready to design your course, you should select a variety of learning materials and activities.

Remember to select activities that will allow students to practice skills needed to meet your module and course outcomes. Learning materials should be aligned with outcomes as well.

The collection of materials and learning activities you incorporate into your course is a large part of the learning experience for your students. Utilizing a range of multimedia materials and selecting materials that demonstrate concepts in different ways can help to accommodate learner differences. Be sure to choose relevant materials that are current in the field. Remember that you can promote active learning through providing engaging activities for your students.

Here are some examples of instructional materials and learning activities for you to explore and consider for your course.

Examples of Instructional Materials

- Textbooks and Publisher Resources

- Articles

- OERs

- Presentations

- Audio and Video Clips

- Images, Charts, and Graphs

Examples of Learning Activities

- Discussions

- Written Assignments

- Role Playing

- Educational Games

- Blogging

- Simulations

- Case Studies and Scenarios

- Knowledge Checks and Quizzes

More Tips for Success

- Develop a companion guide to help students think critically about the materials

- Consider implementing new pedagogical strategies (e.g. gaming) to engage learners

- Explore textbook companion resources that may be available

- Collaborate with a subject area librarian to explore available resources to meet your objectives

- Share ideas with other faculty teaching in your discipline

- Encourage student sharing of resources

- Ask for student feedback on the quality, level of engagement, and alignment of materials

- Refresh your materials periodically, to ensure they are current in your field

Working with Images

Why use Images?

Images play an important role in supporting student learning. Graphics can provide an additional way to represent a concept and complement or even enhance the instructional material (Livingston & Shaw, 2017). Hockley and Bancroft (2011) explain that visuals help with recall and comprehension. The most extensive research on the principles of multimedia learning was conducted by Richard Mayer and Ruth Clark. Clark and Mayer (2016) found that students learn better from words and pictures together than from words alone, especially when the images are selected carefully to support the content and are not used for decorative purpose only.

Choosing Images that Support Learning

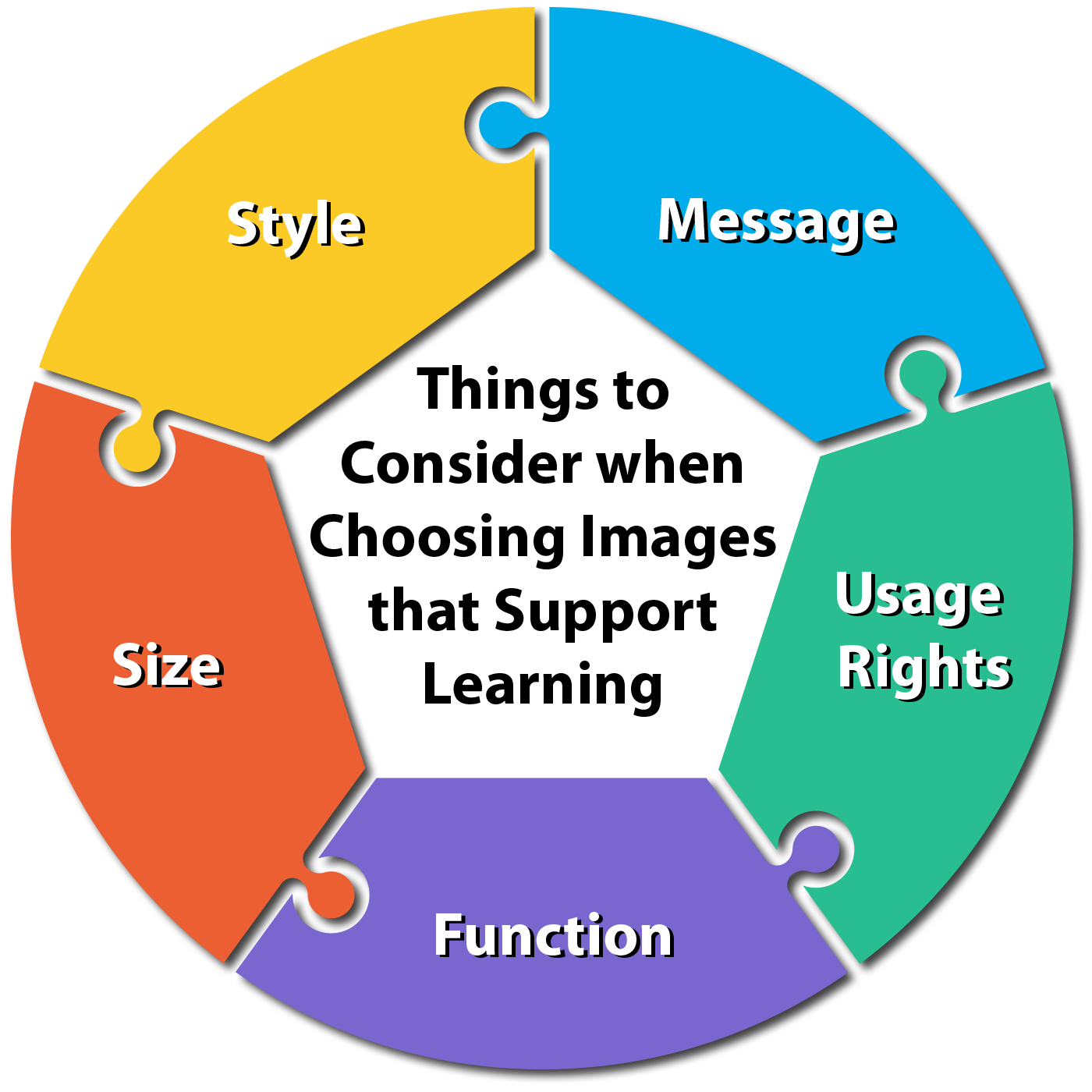

When you start to think about using images for your learning materials, first you should determine the instructional purpose for including images. Diagrams and representational images facilitate a deeper understanding of concepts that may be difficult for students to observe in their daily lives. Graphics such as maps, flowcharts, and animations help students to understand how various parts relate to each other and come together as a whole. Concepts that are illustrated with data should utilize graphs, charts, and other visualization types. Finally, images are used for instructional cues to create consistent style and branding for your course.

Clark and Mayer (2016) created a useful classification of the graphics based on their function. This classification can be used as a guide for selecting images that support learning. It is recommended to minimize the use of decorative and representational images (Greenwood, 2017).

|

Graphic Type |

Description |

Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Decorative | Visuals added for aesthetic appeal or humor | Picture of a question mark in the discussion forum |

| Representational | Visuals that illustrate the appearance of an object | Screenshot of a software application, screenshot of a form |

| Organizational | Visuals that show qualitative relationships among content | Maps, flowcharts, hierarchies, animations |

| Relational | Visuals that summarize quantitative relationships | Bar graphs, histograms, scatter plots |

| Transformational | Visuals that illustrate changes in time or over space | Steps in the process or procedure |

| Interpretive | Visuals that make intangible phenomena visible and concrete | Illustration of a theory, a principle, or cause-and-effect relationships |

- Size – The image size and resolution must be appropriate for your materials.

- Message – Make sure the image conveys the information and emotions that are relevant for your instructional purpose.

- Style – The style of graphics should be consistent across your course materials.

- Usage rights – Make sure the images are free to use. There are different kind of rights attached to the images, so the best approach is to assume all graphics are copyrighted until proven otherwise (Livingston & Shaw, 2017). Some of the safest types of images to use are the ones in the public domain, which means these images can be used freely without the permission of the former copyright owner. Another option is to use Creative-Commons-licensed content with proper attribution and usage of the content.

Finding Free-to-Use Images

When incorporating images into your work, always make sure you obtained them legally. If you simply save an image randomly off the Internet, the chances are that somebody owns that image and you are using it illegally. Here are some sources of images that are freely available for use:

- Pixabay contains only public domain deed images, which constitutes a copyright waiver. Anybody may use images from Pixabay free of charge without attribution. For more details, review Pixabay Simplified License.

- Unsplash has a collection of over 1 million high resolution images that are free to use. Attribution is appreciated but not required.

- Flickr is a crowdsourced image platform. When using images from Flickr, you should be mindful of their copyright license and attribute the images to their authors. You can search Flickr by a specific Creative Commons Licence or by a Public Domain Dedication.

- Wikimedia Commons contains Creative Commons images whose licenses are clearly listed by the image, so there is never any confusion about how to reuse an image.

Working with Multimedia

E-Book available from Library (SUNY Empire Log-in Required)

When you have selected content, be sure to consider the next step: Assuring Accessibility

Resources

Barr, R. B. & Tagg, J. (1995). From Teaching to Learning: A New Paradigm for Undergraduate Education. Change, 27(6). Retrieved from https://usm.maine.edu/sites/default/files/facultycommons/BarrandTagg%20from%20teaching%20to%20learning.pdf

Borup, J., West, R. E., & Graham, C. R. (2012). Improving online social presence through asynchronous video. Internet and Higher Education, 15, 195-203. Retrieved from http://www.northeastern.edu/nuolirc/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/video-and-instuctor-presence-.pdf

Connell, G. L., Donovan, D. A, & Chambers, T. G. (2016). Increasing the Use of Student-Centered Pedagogies from Moderate to High Improves Student Learning and Attitudes about Biology. CBE Life Sciences Education, 15(1), doi: 10.1187/cbe.15-03-0062. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4803092/

Frymier, A. B., & Shulman, G. M. (1995). “What’s in it for me?”: Increasing content relevance to enhance students’ motivation. Communication Education, 44(1), 40–50. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1080/03634529509378996

Muller, K., Gradel, K., Deane, S., Forte, M., McCabe, R., Pickett, A. R., Piorkowski, R., Scalzo, K. & Sullivan, R. (2019). Assessing Student Learning in the Online Modality. National Institute for Learning Outcomes Assessment. Retrieved from https://www.learningoutcomesassessment.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/Occasional-Paper-40.pdf

Nicklen, P., Rivers, G., Ooi, C., Ilic, D., Reeves, S., Walsh, K. & Maloney, S. (2016). An Approach for Calculating Student-Centered Value in Education – A Link between Quality, Efficiency, and the Learning Experience in the Health Professions. PLOS ONE 11(9): e0162941. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0162941

Pacansky-Brock, Michelle. (2014, March 26). How to Design Your Online Course. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=E12H1NUDkT0&feature=youtu.be

UNTUNT Teaching Commons. (n.d.). Retrieved June 17, 2020, from https://teachingcommons.unt.edu/teaching-essentials/online-course-design/selecting-content-your-online-course

Wiggins, G., & McTighe, J. (2005). Understanding by Design (2nd Ed.). Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Evans, R., & Champion, I. (2007). Enhancing online delivery beyond PowerPoint. The Community College Enterprise, 13(2), 75-84.

Hopper, K., & Waugh, J. (2014). PowerPoint: An Overused Technology Deserving of Criticism, but Indispensable. Educational Technology, 54(5), 29-34. Retrieved May 4, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/44430303

Dixson, M. d. (2012). Engaging the Online Learner: Activities and Resources for Creative Instruction, Updated Edition. NACTA Journal, 56(2), 99-100.

Wyatt, J. L. (2014). Engaging the Online Learner: Activities and Resources for Creative Instruction. Adult Learning, 25(2), 74-75.

CC BY 4.0 Attribution: Online Learning Consortium, Inc. used and modified.

Hockley, W. E., & Bancroft, T. (2011). Extensions of the picture superiority effect in associative recognition. Canadian Journal of Experimental Psychology, 65(4), 236-244.

Community Team. (n.d.). 7 Ways to Use Graphics for Learning – E-Learning Heroes. Retrieved May 12, 2020, from https://community.articulate.com/articles/7-ways-to-use-graphics-for-learning

Greenwood, J. (2017). Mayer’s principles for multimedia learning. Retrieved May 12, 2020, from http://instructionaldesign.io/toolkit/mayer/

Livingston, K., & Shaw, A. (2017, May 30). Using Graphics in Online Courses – Center for Teaching and Learning: Wiley Education Services. Retrieved May 12, 2020, from https://ctl.wiley.com/using-graphics-in-online-courses/

Mayer, R. E. (2014). Cognitive theory of multimedia learning. In R. E. Mayer (Ed.), Cambridge handbooks in psychology. The Cambridge handbook of multimedia learning (p. 43–71). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139547369.005

Clark, R. C., & Mayer, R. E. (2016). E-learning and the science of instruction: Proven guidelines for consumers and designers of multimedia learning (4th ed.). Pfeiffer/John Wiley & Sons.