Getting Started with Design

Writing Outcomes that Support Student Success

Research and Course Design Checklist for Online Compressed Courses

SUNY Empire Online Quality Course Checklist

The resources below are intended to be followed in order as the recommended process for getting started with course development.

Using Backwards Course Design

Understanding by Design, by Grant Wiggins and Jay McTighe, offers a framework for designing courses and content units called “Backward Design.” Instructors typically approach course design in a “forward design” manner, meaning they consider the learning activities (how to teach the content), develop assessments around their learning activities, then attempt to draw connections to the learning goals of the course.

In contrast, the backward design approach has instructors consider the learning goals of the course first. These learning goals embody the knowledge and skills instructors want their students to have learned when they leave the course. Once the learning goals have been established, the second stage involves consideration of assessment. The backward design framework suggests that instructors should consider these overarching learning goals and how students will be assessed prior to consideration of how to teach the content. For this reason, backward design is considered a much more intentional approach to course design than traditional methods of design.

Grant Wiggins – Understanding by Design (1 of 2) – An 11 minute video with Educator Grant Wiggins leading a workshop at Avenues on Understanding by Design (UbD), a framework for improving student achievement that helps teachers clarify learning goals, devise assessments that reveal student understanding, and craft effective learning activities.

Grant Wiggins – Understanding by Design (2 of 2) is a 15 minute video that continues the workshop talk.

Understanding By Design – Guidebook with templates: Clicking this link will download this guidebook as a Microsoft Word document.

Writing Outcomes that Support Student Success

Learning outcomes guide the instructor in the selection of the content and instructional strategies, the development of formative and summative assessments and evaluation of learner achievement. Learning outcomes also set the foundation for the rest of the course and are integral to the concept of alignment.

Types of Learning Outcomes

Each level of activity has its own set of learning outcomes. If a learning activity has a purpose, it has a learning outcome. We associate learning outcomes with assignments, with learning modules, courses, programs, even schools. For the purpose of online course design, we will limit our scope to course-level and module-level learning outcomes.

Course Learning Outcomes

The course outcomes are broad statements of what the students will be able to do when they have completed the course.

Some examples of course learning outcomes are:

- Evaluate diversity’s impact on organization effectiveness and its potential for increased performance

- Interpret geologic maps and geologic cross-sections

Module learning outcomes

Module-level outcomes are statements of knowledge and skills the students can expect to attain as a result of engaging in the learning activities of a module. Module learning outcomes are more specific than course learning outcomes and they should tie back to the course outcomes. Module objectives are steps the students must achieve to be able to reach the course objectives.

To illustrate the relationship between the course and module learning outcomes, let’s think about baking a cake as our goal. The course outcome is then:

- Bake a cake.

The learning outcomes would then be:

- Measure ingredients.

- Mix ingredients.

- Set oven temperature.

- Identify the point of “done-ness” of a cake.

Based on the desired pacing of our course, several of these module-level objectives might be accomplished in one module (e.g., it might make sense to teach ingredients measuring and mixing in one module, setting oven temperature in another module, and identify the doneness of a cake in yet another module), or, we can address one objective per module.

Measurable Outcomes

Measurable outcomes are the specific statements that describe what the student is able to do after completing a course. They include verbs that describe actions rather than thoughts or feelings. For instance, consider:

“Students will analyze legal pros and cons of the Death Penalty,”

versus

“Students will develop critical knowledge of the Death Penalty.”

One important rule to follow is that the objective prefigures the evaluation. You measure what the objective says. Use action verbs and include specific conditions that describe to what degree the students will be able to demonstrate mastery of the task. Using the example objectives above, how would you measure if the students have developed critical knowledge (the second objective)? Is there a test for it? An assignment? Most likely you wouldn’t find a test that measures the development of critical knowledge. On the other hand, an analysis (included in the first sample outcome) is a measurable concept.

Some examples of measurable outcomes:

- Given a set of laboratory data and patient history, correctly diagnose the disease.

- Review a business plan and develop project management graphs and establish milestones.

- Identify elements of editing, including composition, setting and lighting.

Some examples of non-measurable outcomes:

- Complete M5 Quiz. (A quiz is an action item, not an objective. It is not a student’s goal to be able to complete a quiz, but by completing a quiz, the student will show you that they are able to identify, describe, analyze, etc. the subject of the course.)

- Appreciate the difference between ‘hazard’ and ‘risk’. (How would you measure if a student appreciates something? For this outcome, it might be more appropriate to ask the student to explain the difference between the two, not necessarily appreciate.)

How to Write Learning Outcomes

Each course should have 3-6 learning outcomes.

Step 1

First, you should write down 3-6 major pieces of knowledge, skill or attitudes/values that a student should gain or know at the end of the course. Focus on overarching or general knowledge and/or skills (rather than small or trivial details).

Step 2

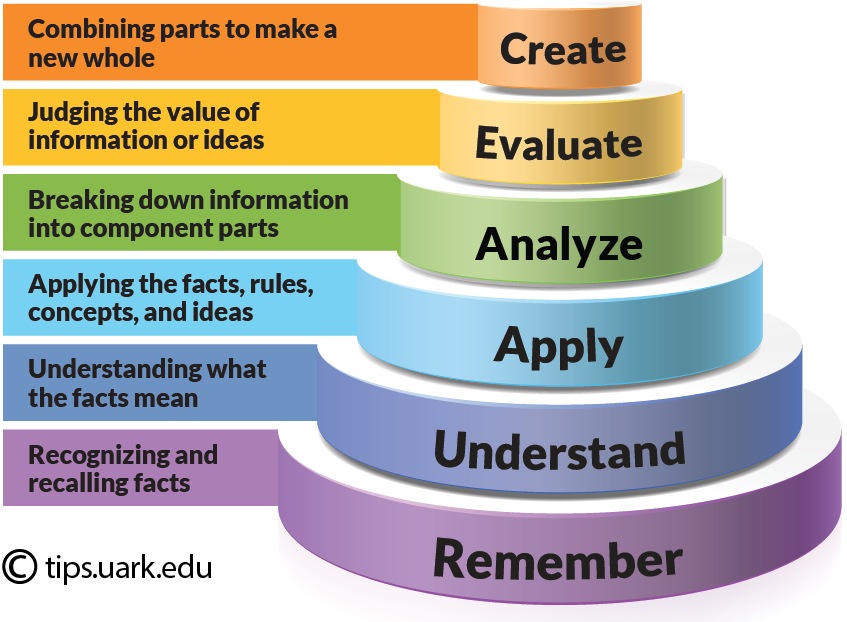

Next, take each statement from Step 1 and choose an action word from Bloom’s Taxonomy (see below) that best describes what the student must do to demonstrate whether or not the student has gained the expected piece of knowledge or skill. Keep in mind that the instructor will need to be able to observe that the student gained the knowledge and measure the level of the student’s success. You are creating statements that describe the learning, NOT the activities. Remember to write the outcomes broad enough to accommodate changes in course content over time so that you can keep course maintenance low (e.g., if you write an outcome that says the students will analyze the supply and demand theory through a multimedia project, once the objective is in the “officially” in the course catalog, all of the future course iterations will have to use a multimedia project for the theory of supply and demand).

Step 3

Rewrite each statement into a one-sentence learning outcome that is clear, observable, and measurable. Make sure you use an action verb that targets the desired level of performance (use some higher order thinking skills for upper level courses).

Scaffolding Learning

In course design, scaffolding refers to the strategy of breaking down a larger assignment into smaller assignments that focus on building the skills or types of knowledge students require to successfully complete the larger assignment. We use the term scaffolding because of the similarity between the construction scaffolding supporting workers working on a building and the supporting function of the partial assignments towards the more complex final assignment.

An example might be a research paper. For a research paper, students have to narrow down their topics and formulate a research question, find and read related sources, synthesize their findings and draw conclusions, outline the paper, write a paper draft, and finalize the paper. It is a good practice to scaffold assignments of this complexity. The preliminary steps (research question formulation and literature review) might be included in a smaller assignment (or even two). The structure of the assignments might then be as follows:

- Module 1 Written Assignment – Research Paper (Research question)

In this assignment, select the angle from which you would like to research the topic of this course, and write out the research question to which you will attempt to find an answer in the research paper. - Module 3 Written Assignment – Research Paper (Literature review)

For this assignment, review the existing literature on the topic of your research paper. Synthesize your findings into a cohesive essay with arguments and counter-arguments. Make sure you appropriately cite your sources. You are required to use at least 6 scholarly sources for this paper. - Module 7 Written Assignment – Research Paper

This assignment is the final step in your research paper writing process. Here, you will combine parts of your previous submissions with the conclusions and recommendations you draw from your literature review and your argument analysis. Your research paper should contain these elements:

- Introduction

- Problem description

- Research question(s)

- Literature review

- Discussion

- Recommendations

- Conclusion

Course Structure/Sequence

Now that you have your course learning objectives determined, you can start creating your course outline and more specifically – start thinking about the topics you are going to cover to meet the objectives.

You can use a course map outline (file 35kB) to help you sequence the course. There are different methods for sequencing within a course as described in the table below, but overall courses should build towards greater complexity, starting with component pieces and working towards synthesis and integration. On other words, move from simple to complex, from known to unknown, from or concrete to abstract.

Methods for Sequencing within a Course

| Method | Description |

|---|---|

|

Topic

|

This method can be used when the topics can be studied in any order. |

|

Chronologically |

An approach that might well apply to a history course but could even be used for a math course when looking at how a topic has developed over time. An example of this can be found in Toeplitz (1963). |

|

Place |

For example, you might work outwards from the home to the world or work from the micro scale (inside a cell) to the macro (the whole organism). |

| Cause and Effect | Here you might start with a phenomenon and explore its causes and origins. |

| Structural Logic | In this case you follow the logic of the subject. Math is often taught like this. |

| Problem Centered | In this case you identify a problem and explore its solution (e.g., how do animals survive severe weather?). |

| Spiral | In the spiral approach, the same material is revisited several times at increasing depths. |

| Backwards Chaining | Here you start with the end result and gradually work backwards through the course to explore how that end result is achieved. For example, in building a spreadsheet, you could start with a finished spreadsheet and set some exercises on using and critiquing it. Through doing this, learners start with an overall understanding of a spreadsheet and then gradually develop a deeper understanding of how it is constructed. |

| A Loose Networked | Here you start with the end result and gradually work backwards through the course to explore how that end result is achieved. For example, in building a spreadsheet, you could start with a finished spreadsheet and set some exercises on using and critiquing it. Through doing this, learners start with an overall understanding of a spreadsheet and then gradually develop a deeper understanding of how it is constructed. |

| A PERT Network | PERT networks are usually found in project management, but they can be used to sequence the topics in a course. The idea of dependency is central to PERT networks. In project management, ‘dependency’ means that one task cannot be started until another has been completed. In course planning, ‘dependency’ means that one topic cannot be studied before another has been mastered. Using PERT networks is only practicable if you have access to some suitable project management software. |

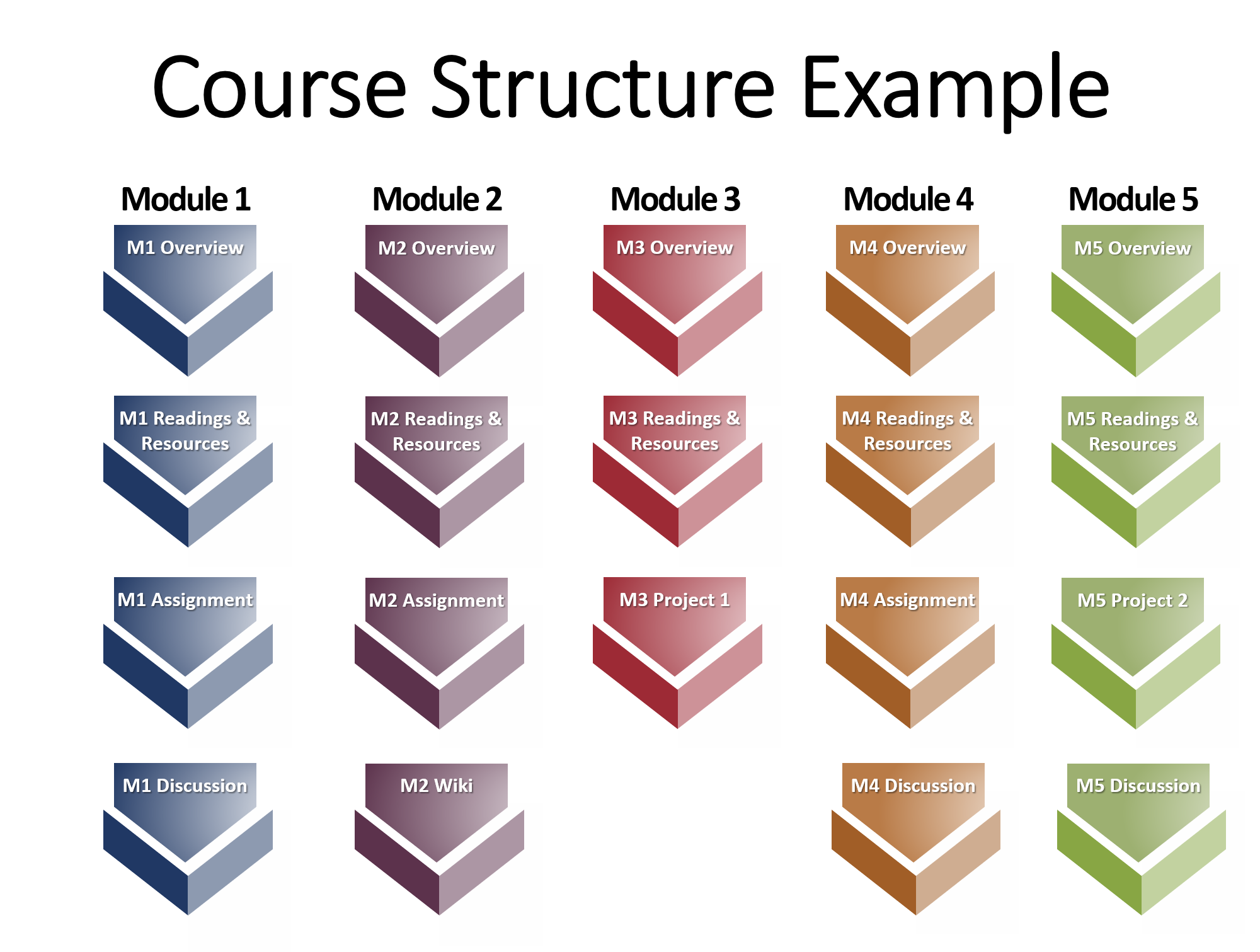

Regardless of the sequencing methods, the course should be well-structured and consistent. With a well-structured course, students know exactly what they need to learn, what they are supposed to do to learn this, and when and where they are supposed to do it. Students studying online will almost certainly study in a more random manner than students attending classes on a regular basis. Instead of the discipline of being at a certain place at a certain time, online students still need clarity about what they are supposed to do each week or maybe over a longer time period as they move into later levels of study. What is essential is that students do not procrastinate online and hope to catch up towards the end of the course, which is often the main cause of failure in online courses (as in face-to-face classes).

Best Practices for Structuring your Course:

- Consistency – the course layout and terminology should be consistent from course to course and within the course. For instance, if there are written assignments in the course, follow the same naming convention for all of them within the course. Also make sure to follow any organizational requirements set by the program or department such as course layout and common information or resources listed within a certain area of the course.

- Chunking – once you have learning activities that will be required for each learning objective, you will be able to look at the sequence of topics to cover together with the necessary learning activities to see how they fit into larger, meaningful “chunks” of learning. Structuring content in small chunks helps learners solidify the relationships between concepts, especially if you use subtitles to provide an easy guide.

- Balanced Workload or Pacing – as your content is in the proper sequence, in the right chunks, you can start to think about how to help learners’ pace themselves so that the learning experience does not get to be overwhelming. It is at this point that you start to think in terms of how much work students can realistically do in a week, for example.

SUNY Empire Online Quality Course Checklist

Download the SUNY Empire Online Quality Course Checklist

This online course quality rubric has been adapted from the Open SUNY Course Quality Rubric (OSCQR). The OSCQR Rubric, Dashboard, and Process are made available by the Online Learning Consortium, Inc., under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC By 4.0).

Now that you have started your course design, you are ready for the next step: Determining Learning Activities

Research and Course Design Checklist for Online Compressed Courses

Compressed, 8-week courses, deliver student success with little cost and investment and it is a growing trend on SUNY and other College campuses. Some research suggests that offering compressed courses increases both completion rates and student success. A more in-depth look at the research is included at the end of this document.

Considerations for Compressing Courses from 15 to 8 Weeks

Design

- Break the course into 8 one-week modules. Keeping students on track can be a greater challenge when the course is moving at a faster pace. Providing shorter, consistently-spaced modules helps students manage their time and stay motivated.

- Make sure students are prepared to use learning tools. In a shorter course, students can fall behind quickly if they can’t access the learning tools at their disposal right away. Consider short activities in the first few days of the term that will help students assess and build their skills for using the learning management system, library, and other relevant academic supports.

Content

- Bite-Sized Chunks– a 4 credit course over eight weeks, calculates to 22 hours a week that a student should be engaged with academic content and activities. This means students should be reading or completing learning activities and assessments 3-4 hours each day, 6 days per week (for a 4 credit course). To keep students paced, motivated, and engaged offer some type of learning activity or assessment they must submit (even if very small) at least 2 times a week, but only one major activity per week.

- Vary the methods of knowledge dissemination (video lectures, text lectures, articles, videos, podcasts) thereby preference for learning and introducing variety to keep students engaged. Keep in mind accessibility (closed captioning, reading order, color contrast, etc.) when finding or developing various resources.

- Example: Say it with a Visual - Get creative with visual design, graphics, live-action videos or infographics. This can be an ideal way to condense what would be a lot of long, boring text into something that feels manageable and engaging to the learner. Grab videos too! Choose bulleted lists over tables.

Resources

- When possible, use OER/Zero Cost resources during the first week to accommodate late registrants or other students who still awaiting textbook access.

- Ensure appropriate student engagement with instructor by building community (ex., Instructor Welcome Videos, Icebreakers, and student surveys) to get to know student and establish baseline knowledge. Faculty may also consider synchronous components (such as office hours) to infuse opportunities for engagement.

- Learning Activities/Assessments may need a redesign to accommodate flexibility in the pace of learning and offer immediate feedback. Turn existing essays or discussion forums into quizzes (multiple-choice, T/F, and/or fill-in-the blank) for immediate feedback. Reduce discussion forums to 1 forum every week.

- Balance assessments to manage instructor workload and allow for timely feedback (mix of formative and summative) use auto-graded quizzes, peer review, rubrics, short quizzes, midterm, and a final exam. Quizzes should tightly align to the online course outcomes and content.

- Add rubrics- rubrics decrease the grading time for instructors and have proven to increase student satisfaction and promote self-assessment.

- Decrease the number of activities with graded submissions- only have students complete the assessments that are reasonably deemed the core knowledge that students “need to know”. There can be activities that ask students to reflect, complete a quick survey, state a favorite quote from the reading, etc. – these are low stakes and provide a way to make sure students are doing the readings and staying on task.

Assignments/Activities

Not all courses are a candidate for compression, though. Some courses will require revisions to accommodate a shorter term.

Learners, the instructor, and institute can benefit from compressed courses. The following table outlines benefits for different stakeholders based on an 8-week model:

|

Stakeholder |

Benefits |

|---|---|

|

Learner |

|

|

Instructor |

|

|

Institution |

|

Resources

Austin, M., & Gustafson, L. (2006). Impact of course length on student learning. Journal of Economics and Finance Education, 5(1), 26–36.

Bowen, Ryan S., (2017). Understanding by Design. Vanderbilt University Center for Teaching. Retrieved [3/26/20

https://tips.uark.edu/using-blooms-taxonomy

Carnegie Mellon University. (n.d.). Course Content & Schedule – Eberly Center – Carnegie Mellon University. Retrieved June 16, 2020, from https://www.cmu.edu/teaching/designteach/design/contentschedule.html

Daniel, E. L. (2000). A review of time-shortened courses across disciplines. College Student Journal, 34(2), 298-308.

Developing & Teaching Online Courses by Commonwealth of Learning

Freeman, R. (2005). Creating learning materials for open and distance learning: A handbook for authors and instructional designers. Vancouver: Commonwealth of Learning.

(2018, January 26). 9 Great Concept Mapping Tools for Teachers and Students. Retrieved June 16, 2020, from https://www.educatorstechnology.com/2018/01/9-great-concept-mapping-tools-for.html

Gamboa, B. R. (2013). Impact of course length on and subsequent use as a predictor of course success [Institutional Effectiveness Report]. https://www.sanjac.edu/sites/default/files/Crafton-Hills-CC-Compressed-Course-Study.pdf.

Kretovics, M. A., Crowe, A. R., & Hyun, E. (2005). A study of faculty perceptions of summer compressed course teaching. Innovative Higher Education, 30(1), 37-51. doi:10.1007/s10755-005-3295-1.

McDaniel, E., Roth, B., & Millar, M. (2005) Concept mapping as a tool for curriculum design, Issues in Informing Science and Information Technology Education Joint Conference,505–513, Flagstaff, AZ, June 16–19, 2005.

The Online Course Mapping Guide by Teaching + Learning Commons Digital Learning UC San Diego

Scott, P. A., and Conrad, C. (1992). A Critique of Intensive Courses and an Agenda for Research. In Higher Education: Handbook of Theory and Research, edited by John C. Smart. Agathon Press.

Seamon, M. (2004). Short and long-term differences in instructional effectiveness between intensive and semester-length courses. Teachers College Record, 106, 635-650. 10.1111/j.1467-9620.2004.00360.x.

Sheldon, C., & Durella, N. (2010). Success rates for students taking compressed and regular length development courses in the community college. Community College Journal of Research and Practice, 34(1–2), 39–54.

Stein, R. (2016). Amarillo College divided on condensed courses. https://www.amarillo.com/news/latest-news/2016-07-14/ac-divided-condensed-courses

Thompson, S. (2021). Research and course design checklist for compressed online courses.

Wlodkowski, R. J. Enhancing Adult Motivation to Learn: A Comprehensive Guide for Teaching All Adults. (rev. ed.) Jossey-Bass, 1999.

Adapted from the Research and Course Design Checklist for Compressed Online Courses by Sonja Thomson. This document is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License