How Does Your Garden Grow? Sweetly

by Helen Susan Edelman

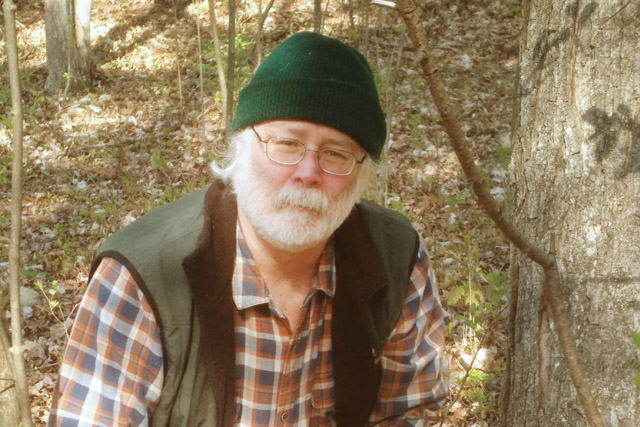

John Hughes ’81 says, “In a perfect world, everyone would contribute to feeding themselves.

Knowing how to grow your own food is a good idea. You can control the purity, you know where it comes from and it’s delicious. As I have become increasingly aware over time of the worldwide population crisis and the food crisis that goes with it, my commitment to serious gardening has evolved.”

A native and current resident of the Albany, N.Y. region, Hughes has a B.S. in Video Production from the college and an M.S. in Technical Communications from Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, where he was a founder of the Rensselaer Satellite Video Program. He joined the staff at Empire State College in 2005 and now serves as director of media production and resources in the Office of Communications and Government Relations.

When he’s not at work, he’s in the garden – two acres on his own property and additional space in a community garden. Hughes grows cucumbers, beans, tomatoes, cantaloupes, pumpkins, potatoes, carrots, herbs and “every kind of pepper imaginable, including Cubans, which are a 10 on a one-to-10 scale for being hot.”

He tends to his rural “hobby farm,” as he refers to it, at night and on weekends throughout the growing season to keep up with the weeds and the harvest. In fact, the effort begins even before the plants are in the ground, in his house, under lights.

The process can be tricky. One year, he produced an unplanned 500 pounds of tomatoes by using rabbit droppings as fertilizer, instead of horse or cow manure. “I made a lot of tomato sauce, tomato soup and canned tomatoes and ate them for dinner every night for months,” he recalls, somewhere between a laugh and a grimace. “I gave a lot away, too. Fresh food is a gift everybody loves to get.”

More recently, Hughes’ imagination was ignited by another food-related pursuit: maple-sugaring. Along with a couple of friends, he has been tapping maple trees on both a friend’s forested land and a smaller tract behind his own house, gathering the sap, lugging it to an evaporator in a shed built just for the purpose, boiling it to exactly the right temperature for exactly the right amount of time and bottling it for immediate use or storage. They make about 40 gallons of the golden liquid a season, tapping 120 trees.

“You’ve got to tap the tree at just the right time, when it’s 40 degrees in the day and 20 at night, and boil it carefully, so it’s neither too watery, nor burned,” he explains. He also makes cookies and candy and once, when he wasn’t vigilant, he overcooked the syrup, accidentally producing maple sugar. Another time, when he decided to test his technique in his kitchen, he almost burned down his house, confirming, “You can’t leave the sap to boil on

its own.”

Hughes actually loves the flavor of the tree sap “as is,” before he cooks it. “It’s indescribably sweet,” he says, “except it is very sticky.” Some people like amber syrup, some like it dark, he notes. “Neither is ‘better’. It’s strictly a matter of taste.” (He prefers amber.) The work is grueling and time-intensive, stretching over weeks in the right weather: drilling, attaching plastic tubes, carrying sap and making up batches.

“I love the transformative nature of it: raw sap plus heat becoming food,” says Hughes. “It’s a renewable way to harvest resources without destroying them.”

Photography by Dee Hughes